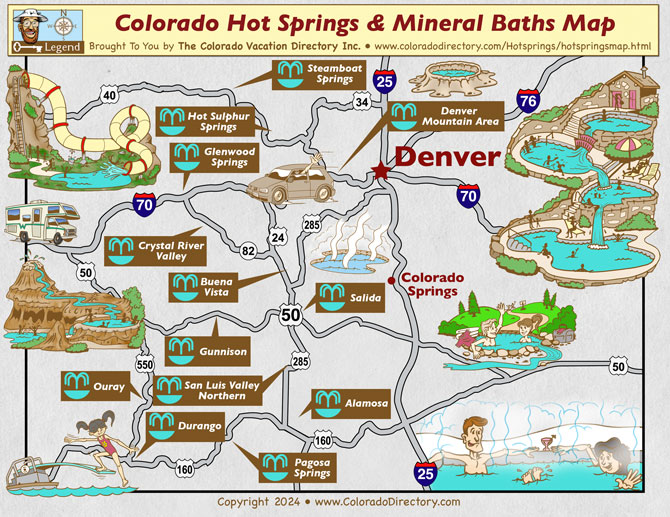

Glenwood Springs was first. The strong smell of sulfur and the scratch of concrete on our bare feet. I think it may be more bougie now, but it is still hot. I remember thinking that the first pool was so hot it may have literally touched the earth’s core. My young siblings and I dared each other to jump in, or even to dip a toe, before we headed to the milder, larger warm pool that seemed to go on forever. Apparently its the largest hot springs pool in the world!

“I can still touch here,” we would exclaim to one another and to our parents, as we bobbed along all the way to the deep end, its diving boards, and an inevitable sunburn in the high-altitude swim.

My young husband and I ended up back in Glenwood again for our honeymoon. It was unexpected, a sort of punt after the cruise line we’d booked went bankrupt. We kept returning wedding gifts at the Glenwood Walmart to extend our stay at the honeymoon suite at the Silver Spruce Inn and then cheaper Starlight Lodge. A set of six glass tumblers and some mixing bowls afforded us a few more days of hiking, soaking, and fine dining at the Village Inn. I think couples plan more today and have more money. But are they the happier for it? Debatable.

We were married in late December, and if you’ve never been in a Colorado hot springs in winter, know this: it’s magic. Pillows of steam rise from the water, wrapping swimmers in mystery and privacy as they glide through the warm, mineral-rich pool. Pure joy.

Three years later, we landed in Norwood, Colorado, not far from Ouray, another hot springs haven. We’d often drive the hour to soak in the mineral baths while our preschool daughter swam circles around us. We’d lean back, relax, and scan the red cliffs for mountain goats.

Another daughter later and we headed again to Glenwood, and then more regularly down from Grandma and Grandpa’s place in the center of the state to Mt. Princeton Hot Springs near Buena Vista. They had a frequent swimmer punch card!

At that time, Mt. Princeton wasn’t much—just a cave-like reception area, a basic rectangular pool, and a path down to Chalk Creek, where the real magic happened. Hot water bubbles up beneath the sandy creek bed, and visitors build rock pools right in the stream, mixing hot and cold flows to find the perfect soak. The kids loved experimenting, damming one side, letting cold water in the other. It’s a little more fancy now, and definitely much more expensive, but the creek is still the best part.

In more recent years, we’ve added new springs to our travelogue. Pagosa Springs, near Durango, charmed us with its location right in town but somehow still holding onto a nature vibe. Strawberry Hot Springs, near Steamboat, delivered an entirely different experience—hippie vibes, clothing optional after dark, and a sketchy unisex changing room with raggedy curtains. After a day of skiing we braved the snowy stairs on prickly bare feet to sink into the steamy and crowded, but warm and lovely pools.

Our favorite hot spring discovery lately is the redeveloped Iron Mountain Hot Springs, the second major spring in Glenwood. It features over a dozen small pools made of red rock, sand, and pebbles, blending into the high desert aesthetic and offering unique temperatures marked with metal signage. Regular adjustments with cool Colorado River water offset the natural 112°F heat.

The best part? Choice. Want to stay in a toasty 105°F? Done. Prefer a milder 99°F? Just down the walkway. My personal favorite is 103°F. Every body is different.

Some pools are close enough to hear the river; others let you sit and watch it flow by. Bathers soak surrounded by foothills, eagles—and the glow of lights from the big box stores across the water.

We still have plenty of hot springs left to try. So when we find our next favorite soak—I’ll be sure to let you know.

###