Some art is created to dissolve.

Ice sculptures. Sandcastles. Chalk paintings on pavement. Ron and I walked around the Denver Chalk Art Festival this year and glimpsed some wildly colorful works chalked onto the streets. The bold palettes seemed to take their cues from tattoos, or street murals. And, despite the fact that the artists were painting down on the ground, many managed to add enlivening dimensions to their asphalt canvases.

Chalk artistry is one of the most optimistic and free expressions of art. Hours are spent drawing, shading, and adding detail, all for the sake of a creation that disappears within days, maybe hours if it rains. Transient art reminds us that everything will pass. Maybe that’s also why I blog.

Some art wants you to feel something.

Set in the same Denver block as the chalk art festival is the Clyfford Still Museum. I stepped inside this ultra-modern edifice on one of its free days a few weeks ago. It was built specifically to house nearly all the paintings by American artist Clyfford Still (1904-1980).

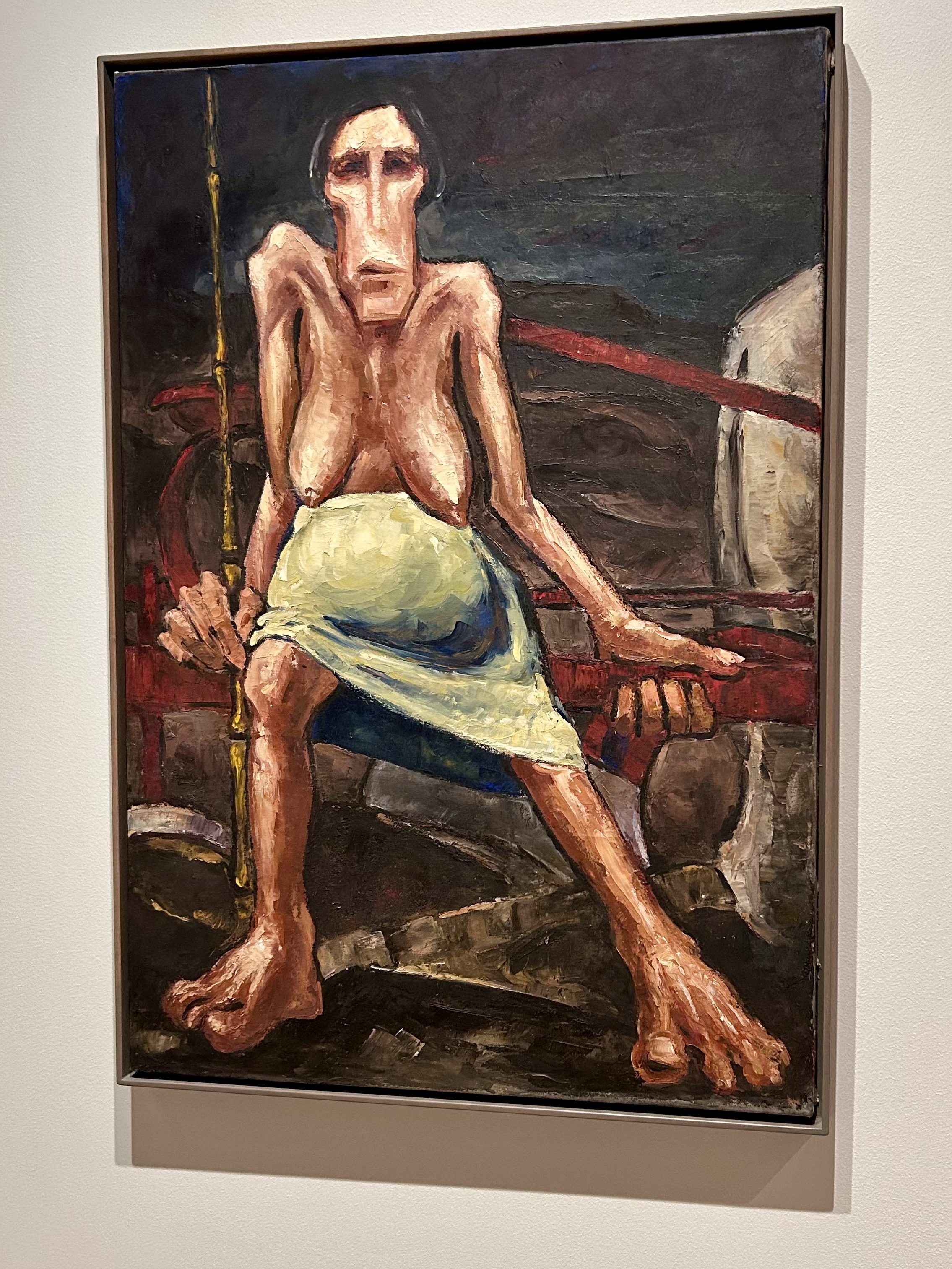

Arranged to show Still’s journey as an artist, the exhibit began with works from The Great Depression era. Still painted horse-faced people whose skin drapes thick over their protruding bones, hands dangling like oars at their sides. Following World War II, Still became an abstract expressionist of the 1950s. He was counted along with Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, and a dozen others in this movement.

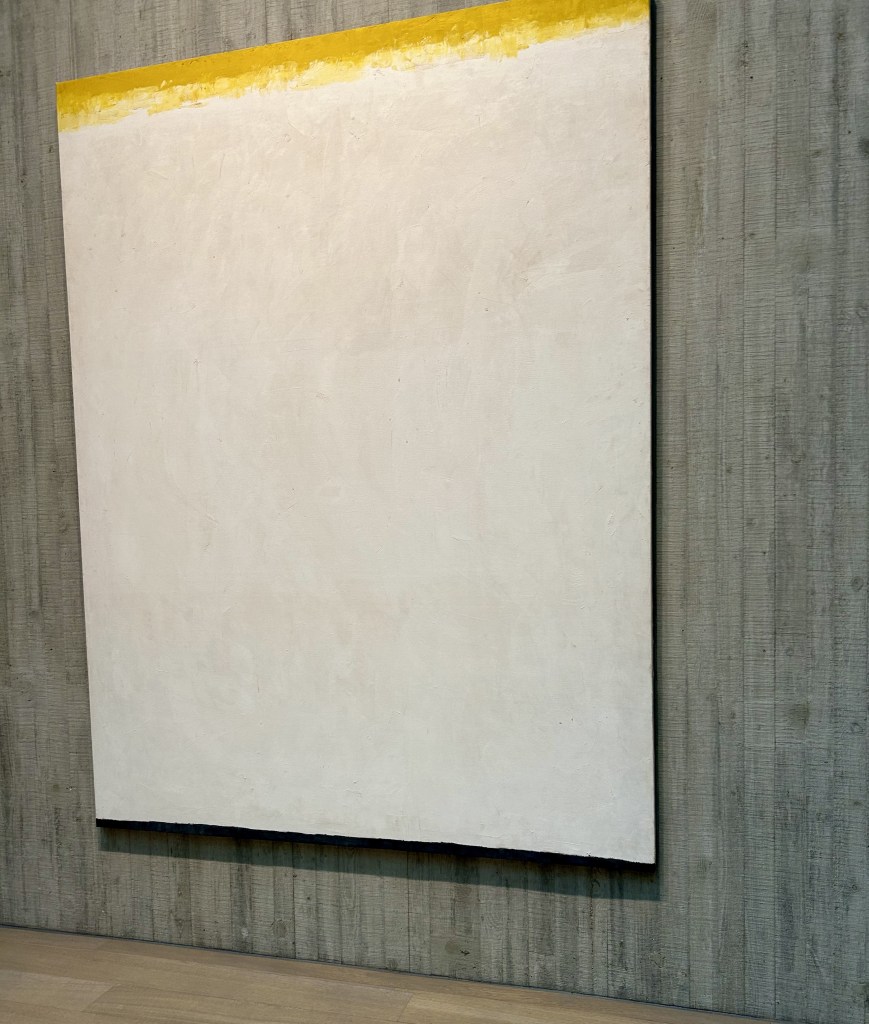

Still used enormous canvases. He was right doing that, I think. Feelings can be big. He painted giant swaths of one or two colors. He used jagged shapes, blocks, and lines. I like the horse-face people better. Abstract art has never compelled me. That doesn’t say as much about abstract art as it says about me.

I related to the woman Still painted who seemed to me to embody the stage of life in which I now find myself; mid-50s, empty nest. Still’s work, PH 416 was like staring into a mirror. The woman sits shirtless for no apparent reason, large breasts hanging down slack and uneven, nipples shelved on a rounded lower belly bulging beneath a green skirt. She’s holding what appears to be a bamboo pole in one massive paw. Her face is long, like the others, and blank; emotionless. Here large toes, feet, and hands no match for her gaunt body, painted sinewy with deep contrasts.

I am her, I think, as I gaze at the painting.

Then, I imagine Still tiring of this woman, and all the long faces. I consider the steps he took from these works to abstract painting. I try to make sense of his interest in art that would provoke emotion in viewers, rather than reveal it in those he painted.

Some art is found.

I wandered back to the bus stop, still thinking about the Still Museum paintings and stopped to notice the bright red poppies, and pale pink peonies guarded by a wrought iron fence at the Center for Colorado Women’s History. Maybe flowers are art. Maybe drawing or painting them is art. Do they convey emotion? Do they elicit it?

I’ve been reading The Supper of the Lamb: A Culinary Reflection by Robert Farrar Capon, and it’s a treasure trove of practical theology. Art and theology are as close as siblings I think, since God is a creator, and we are made in his image. Capon broadens the idea of art for art’s sake to encompass more than art. So, I think food, flowers, paintings, chalk or otherwise, abstract or representational, everything that has been made would be included in what Capon says exists simply for joy.

“The world exists, not for what it means but for what it is.” – Robert Farrar Capon

###